POINTILLISM

The genre of art known as pointillism rightfully begins with one of its earliest theorists and practitioners, French impressionist artist Georges Seurat (1859-1891). Seurat was very much concerned with color and visual theories which he spent the greater part of his short artistic career pursuing. Ogden Rood’s Modern Chromatics as well as Sutter’s Phenomena of Vision were among his chief inspirations.

Seurat produced an amazing number of large pointillist paintings in the brief period in which he practiced the art. There is no doubt as to his labor intensive dedication to his work. His paintings are very atmospheric in the sense of literally capturing his vision of scenes hovering in the very air of existence. His paintings composed of small colored dots diligently applied give a soft, almost pastel effect. The colors blend in the eye of the beholder viewing his canvases. Nor was he alone in this approach. A small school of others followed in his footsteps, including artist Paul Signac.

If the art technique of impressionism essentially fragmented the image in a series of colored splotches and daubs of paint, Seurat’s pointillism further reduced the image to one composed of atoms. In a sense, Seurat’s technique takes impressionism to its logical conclusion. His craft was one of applying the dots with a fine sable brush. He might get two or three dots at most and then wipe the brush clean and apply paint again for several more dots.

As a young boy living in Chicago and having access to the Art Institute’s gallery, I often studied and marveled at Seurat’s large painting Un Dimanche d’ I’lle de la Grande Jutte (often referred to in English as Sunday Afternoon in the Park). I would stand close to thepainting viewing the infinite colored dots, and then stand back at a distance and marvel at seeing how they melded together creating the colors in one’s eye rather than directly on the canvas.

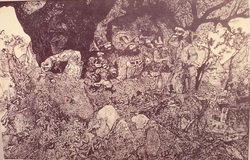

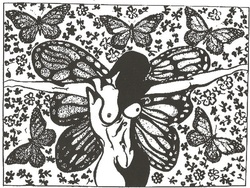

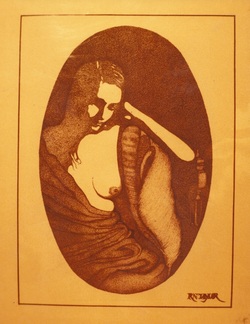

Pointillist technique of course is not relegated to oil painting. It can be accomplished in other mediums as well. My chosen medium was pen and ink - both colored inks as well as monochromatic black India ink and sepia ink, respectively.

I had first become aware of this pen and ink technique from a fellow worker at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago. Peter Solt was a pointillist who did many fine drawings in the technique. He gifted me my first crow-quill pen to try the technique out. He did a lot of illustrations for the underground newspaper The Chicago Seed. As a result of my brief association with him, I did a number of pieces of art for The Seed as well.

I also worked on a much smaller scale than Seurat. Generally the works I did in this technique were 12" x 12" on placard or poster board. Some of the black and white work I did was done on mylar sheet. Mylar, a type of acetate, was user-friendly in the sense that if a blob of ink occurred where the pen hit a wet dot already on the surface, it could quickly be absorbed with tissue and cleaned with a q-tip dipped in ammonia. It is much more difficult to do so on board or paper. It also was more resilient when handled for the use of making prints or serigraphs from the original.

I preferred off-white or tan paper or board to white since it did not glare back at me while under a lamp being worked on for hours and hours. The amount of time spent on each work varied. Some required as much as 300 sit-down hours of labor. Some were finished with three months of intensive work – others took a year or more to reach completion. I kept a sort of time log for many of the works.

Pointillism, when applied to pen and ink technique, is often referred to as stipple-work. My preference for a pen head was a 250 lithographer’s pen. Those were removable quills for a wooden handle. Each pen was dipped into a bottle of ink and then applied. Often I would go through as many as three or four pen tips on a given work as they would wear down flat after such long use.

Progress on a work was very slow; results were slow to realize. One might dot-in an inch or so at a sitting. This type of work develops an immense discipline and patience in the artist. While working on a piece, the whole room would literally disappear from my consciousness (so intense was my focus on the minutae of dot work). It was in effect a form of meditation - deep mediation. Coffee, Vivarin and other stimulants helped to push me on to longer labor and prevent my becoming fatigued. Often I would listen to very fast and hyper music like Nicholai-Rimsky Korsakov’s music of pageantry, such as “Procession of the Tumblers.” It seemed to work well as a corollary to my labors.

But there were other downsides to the pointillist technique beyond the slow progress of work. It was very hard on one’s eye sight. At one point I was working as an industrial engraver. Industrial engraving is also a very visually taxing profession. Everything was gaged down to 10 thousandths of an inch toleration. I would do this for eight hours a day, almost always leaving with a headache and eye strain. Then after work I would resume work on a pointillist drawing at home on a drawing board at the kitchen table or in a small space I had under the back porch of my home. This apparently was more than my eye sight could bear. One day I picked up a newspaper or paperback book to read only to discover that I could no longer focus adequately to read anything in type. All was a blur. That effectively ended my journey in pointillism as well as my career as an industrial engraver. It would be more than a year before I was again capable of reading a newspaper or book again. I dared not return to pointillism again for fear of permanently damaging my sight.

- R. N. Taylor

2011

The genre of art known as pointillism rightfully begins with one of its earliest theorists and practitioners, French impressionist artist Georges Seurat (1859-1891). Seurat was very much concerned with color and visual theories which he spent the greater part of his short artistic career pursuing. Ogden Rood’s Modern Chromatics as well as Sutter’s Phenomena of Vision were among his chief inspirations.

Seurat produced an amazing number of large pointillist paintings in the brief period in which he practiced the art. There is no doubt as to his labor intensive dedication to his work. His paintings are very atmospheric in the sense of literally capturing his vision of scenes hovering in the very air of existence. His paintings composed of small colored dots diligently applied give a soft, almost pastel effect. The colors blend in the eye of the beholder viewing his canvases. Nor was he alone in this approach. A small school of others followed in his footsteps, including artist Paul Signac.

If the art technique of impressionism essentially fragmented the image in a series of colored splotches and daubs of paint, Seurat’s pointillism further reduced the image to one composed of atoms. In a sense, Seurat’s technique takes impressionism to its logical conclusion. His craft was one of applying the dots with a fine sable brush. He might get two or three dots at most and then wipe the brush clean and apply paint again for several more dots.

As a young boy living in Chicago and having access to the Art Institute’s gallery, I often studied and marveled at Seurat’s large painting Un Dimanche d’ I’lle de la Grande Jutte (often referred to in English as Sunday Afternoon in the Park). I would stand close to thepainting viewing the infinite colored dots, and then stand back at a distance and marvel at seeing how they melded together creating the colors in one’s eye rather than directly on the canvas.

Pointillist technique of course is not relegated to oil painting. It can be accomplished in other mediums as well. My chosen medium was pen and ink - both colored inks as well as monochromatic black India ink and sepia ink, respectively.

I had first become aware of this pen and ink technique from a fellow worker at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago. Peter Solt was a pointillist who did many fine drawings in the technique. He gifted me my first crow-quill pen to try the technique out. He did a lot of illustrations for the underground newspaper The Chicago Seed. As a result of my brief association with him, I did a number of pieces of art for The Seed as well.

I also worked on a much smaller scale than Seurat. Generally the works I did in this technique were 12" x 12" on placard or poster board. Some of the black and white work I did was done on mylar sheet. Mylar, a type of acetate, was user-friendly in the sense that if a blob of ink occurred where the pen hit a wet dot already on the surface, it could quickly be absorbed with tissue and cleaned with a q-tip dipped in ammonia. It is much more difficult to do so on board or paper. It also was more resilient when handled for the use of making prints or serigraphs from the original.

I preferred off-white or tan paper or board to white since it did not glare back at me while under a lamp being worked on for hours and hours. The amount of time spent on each work varied. Some required as much as 300 sit-down hours of labor. Some were finished with three months of intensive work – others took a year or more to reach completion. I kept a sort of time log for many of the works.

Pointillism, when applied to pen and ink technique, is often referred to as stipple-work. My preference for a pen head was a 250 lithographer’s pen. Those were removable quills for a wooden handle. Each pen was dipped into a bottle of ink and then applied. Often I would go through as many as three or four pen tips on a given work as they would wear down flat after such long use.

Progress on a work was very slow; results were slow to realize. One might dot-in an inch or so at a sitting. This type of work develops an immense discipline and patience in the artist. While working on a piece, the whole room would literally disappear from my consciousness (so intense was my focus on the minutae of dot work). It was in effect a form of meditation - deep mediation. Coffee, Vivarin and other stimulants helped to push me on to longer labor and prevent my becoming fatigued. Often I would listen to very fast and hyper music like Nicholai-Rimsky Korsakov’s music of pageantry, such as “Procession of the Tumblers.” It seemed to work well as a corollary to my labors.

But there were other downsides to the pointillist technique beyond the slow progress of work. It was very hard on one’s eye sight. At one point I was working as an industrial engraver. Industrial engraving is also a very visually taxing profession. Everything was gaged down to 10 thousandths of an inch toleration. I would do this for eight hours a day, almost always leaving with a headache and eye strain. Then after work I would resume work on a pointillist drawing at home on a drawing board at the kitchen table or in a small space I had under the back porch of my home. This apparently was more than my eye sight could bear. One day I picked up a newspaper or paperback book to read only to discover that I could no longer focus adequately to read anything in type. All was a blur. That effectively ended my journey in pointillism as well as my career as an industrial engraver. It would be more than a year before I was again capable of reading a newspaper or book again. I dared not return to pointillism again for fear of permanently damaging my sight.

- R. N. Taylor

2011