Robert N. Taylor: A Folk Artist in the Postmodern Era

by Joan Hacker

How can the “redefinition of boundaries” in the visual arts, as Lisa Phillips puts it (177), without tearing them down completely, be considered revolutionary? Unless you idealize opportunism and artificiality, the implication that the repackaging of a supposed counter-culture and marketing it to the masses is little more than a path to self-aggrandizement is almost as offensive as John Carlin’s use of the Beatles to illustrate counter-culture music or his statement that Bob Dylan was inspired by his “roots” (179)—if this was the case, Robert Zimmerman would have popularized Klezmer music! While these two might serve well as examples of postmodern appropriation, their era-specific façades and commercial success fail to indicate any deeper exploration of identity within the newly expanded boundaries available to them.

If the 1960s are to possess any true value as a radical period in the history of the visual arts in America, one must turn her or his attention away from the purveyors of vacuous, anonymous art and focus on artists who had the courage to express themselves according to the identity which simply existed within their beings—no matter how unfashionable—through a process, not of redefinition, but of self-discovery.

Robert N. Taylor is one such artist, a folk artist who consciously rejected the path of a conventional, American, white, male yet found little solace in the trends which informed a typical “hippie,” at last finding his own identity upon which he built his unique body of pen and ink drawings. In his own words:

We felt constricted under the thumb of a debased age in which advertised slogans supplanted poetry, contractual agreements replaced love, and televangelism masqueraded as spirituality. Unlike that alien and decadent garb of the Guru cults from the East, the Process[1] had a distinctly Western, Neo-Gothic exterior: Neatly trimmed shoulder length hair and equally neat beards, all set-off by tailored magician’s capes with matching black uniforms. (“Where It All Began”)

Taylor’s father, who, according to Taylor, was “very much a heathen and very anti-Christian,” (Flux Europa) initially fostered this interest in the West and this influence inspires and colors all of Taylor’s creative work.

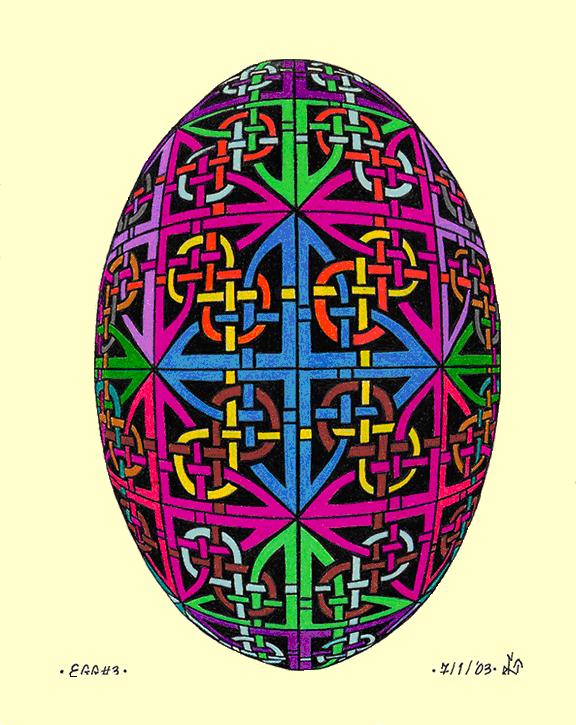

Originally working as a copywriter and art director for a major advertising firm, and then aligning himself with the artist group The San Francisco Visionaries, (Flux Europa) Taylor developed a personal visual language with which to voice his spiritual views. He filtered ancient European symbols through his graphic arts training and the psychedelic sensibility of the time in order to create pieces, which are both timeless and contemporary. The later work Celtique Egg #3 (see figure 1) will serve as our example and help us follow the streams of influence which comprise Taylor’s work and which eventually lead to the heart of his identity as an artist.

At initial viewing, one is overwhelmed by a seemingly incomprehensible tangle of colors and shapes, which, over time, begin to order themselves according to patterns of colors and symbols. This need for a meditative approach by the viewer is intentional and reflects the creator’s own psychological process, which we will explore later. The use of flat colors against a black backdrop reflects the “poster style” popular in the 1960s psychedelic art and which Taylor employed in his professional life. This image could very well be reproduced in large numbers by silk screen as if Taylor and his peers were making a grassroots effort to promote a new age to the public at large.

The colors themselves, however, while bright and vibrating off the page, do not confront the viewer like those of a propaganda poster do. The array of primary, fluorescent, and pastel colors, in fact, prevents the viewer from forming any sort of conclusive bias based on traditional psychological or emotional associations with color and instead draws the viewer into a new kind of world which holds endless possibilities. The use of black as the interior of this “egg” does seem to employ the familiar symbolism of the eternal, though, and as such, echoes the aforementioned sentiment. The colorful lines enclose the eternal egg like a protective layer while providing pathways by which the viewer can explore it.

But is it that eternity appears in the shape of an egg, or do the pathways delineate the eternal through a shape, which is conceivable by man? Is it possible that the paths themselves are eternal? The egg shape of the image suggests a unity of the notions of the eternal and of creation and that by traversing the pathways of creation, man circumnavigates and parallaxes the eternal.

The symbols which create the “paths” on the surface of the black eternal indicate that these paths parallel the destination of eternality itself as well as lead to it: the paths and the destination are nearly synonymous. This is most clearly demonstrated in the frequent references to the Celtic knot and the arrows. Celtic knots are designs which are constructed in a way so that each line element connects back with itself, and are thus unending, a reference to the eternal. Taylor takes this idea further by arranging them side by side in order to create representations of the mathematical infinity sign, ∞. Carrying this concept out on several pattern layers recalls the infinite character of a fractal, the artistic representation of which is also popular in psychedelic art.

Regarding the arrows, they jut out from crosses and point, like road signs, to tiny, black dots, which seem to be doorways into the eternal. In the context of creation, the arrows’ rounded, uneven heads could be interpreted as phallic symbols. Interestingly, the arrows are ringed by the abovementioned infinity signs, essentially creating circles with dots—an ancient sun symbol. The variation of the swastika symbol, which comprises the Celtic knots, reiterates the sun motif and finds its way into many of Taylor’s drawings. Without going into the myriad symbolic associations cultures have and have had with the sun, it is sufficient to consider its cyclic nature.

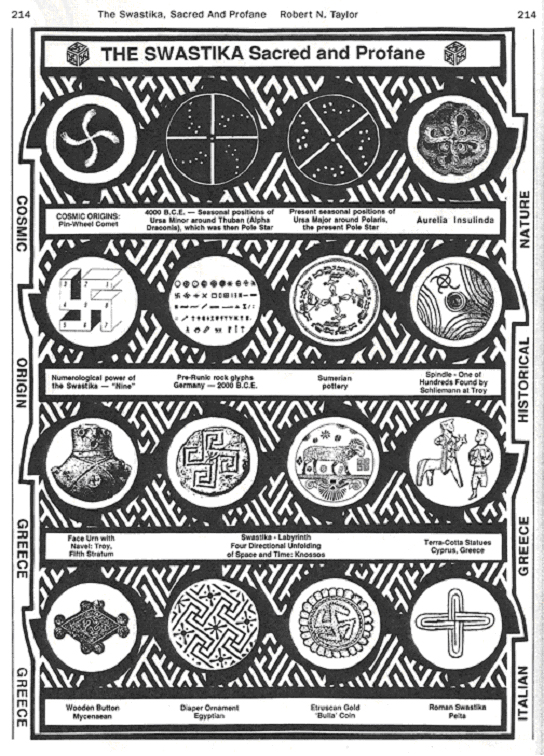

In fact, Taylor has such a fascination with the spinning cross, he outlined its extensive history over ten pages in George Petros’ Exit Collection (see figure 2), in which one notes the swastika’s “cosmic origins” and its meaning as a, “Four Directional Unfolding of Space and Time;” yet such content caused the book to be banned in Germany. So while Taylor was, “…simply showing the longevity of this symbol, and that it got frozen in a fourteen-year time slot…” (Art That Kills, 173) he is aware of the ramifications of his actions. In an interview with Petros he explains, “If I’ve left a path of destruction behind me, it wasn’t intentional per se, but I do like to tweak people…I have the ability to manipulate reality around you.” (Art That Kills, 173) Thus, by reclaiming this appropriated and then stigmatized symbol, Taylor conveys the never-ending turning of time in a way which provokes people, even to the point of gaining attention from a governmental body.

Taylor carries his meditation on eternality through to his pictorial history of another, better accepted symbol: pi. He summarizes, “…the history of Pi is also the story of man’s eternal fascination with the circle, and like the circle, this fascination has no beginning and no end.” (Exit, 195) That the survey of pi lies within a few pages of that of the swastika, it almost seems ludicrous that a couple of lines arranged in a particular order could raise so many concerns, while lines arranged differently, with a nearly comparable impetus behind them, hardly cause notice. Taylor’s interest in diagrams and, in a way, diagramming the universe, seems to be a way for him to carry on the tradition of diagrammatic art made by alchemists, whom he cites as a direct influence. (Flux Europa)

But the use of symbolism in Taylor’s work goes even further: “Symbols can be modified in their meaning, but you can’t suppress them—because they come from within.” (Art That Kills, 173) He further explains in an interview with Flux Europa how the writings of Ezra Pound on Chinese and Japanese characters may have subconsciously influenced his work: Ezra Pound and the Imagist poets sought to refine or distill the meanings of words as precisely as possible, and it is possible to say that a symbol is this concept taken to the extreme.

Similarly, in a personal conversation with the author in 2008, Taylor noted enjoying the challenge of shaping his poems in order to further convey the meaning of his words. He tells Flux Europa, “The first pattern poems I encountered were being done by a very fine poet, Robert Dougherty, who created poems that took the shape of the subject they described. This was all done with a typewriter. Some years later I began doing similar typographical experiments with hand calligraphy and stipple pen technique.” These examples show the interplay between language, character, symbol, and visual representation, and how Taylor, who works predominantly as a poet, bridges his writing and visual work.

Another visual model Taylor uses in his work is the mandala. As geometric diagrams of the universe, mandalas are meditation tools for both those who create them and those who view them. Taylor references Jung and explains, “The making of mandalic art is an attempt to find one's way back to the centre of things; it is a yearning for totality and completeness.” (Flux Europa) So, again, what might first appear to be an incoherent web in the work Celtique Egg #3, is actually the result of a meditative process performed by Taylor, in which he has drawn upon various traditions, incorporated symbols which hold personal meaning, and created a work which can then be experienced by others who may also gain some understanding of the nature of existence according to Taylor.

The egg shape present in the egg series demonstrates a deep respect for the female, which comprises an equal half of the creative process. The role of the female in Taylor’s work is an eternal one, which could, arguably, reflect the progress made during the 1960s in the area of women’s rights yet which is tempered by a more traditional, romanticized, male view of the female. Regarding the inspiration for his writing, which seems to apply to his drawings, he states:

The primary source is the Muse. I do not mean 'The Muse' in a metaphorical sense to describe inspiration in a poetic manner, but in a literal sense - a spiritual guide whose touch bestows the gift of inspiration, a Goddess concerned with poetry and muse-ic. My views are similar to the views of the poet Robert Graves, who believed in a Muse and felt that she was the source of all poetry and poetic inspiration. All traditional, archaic cultures seem to have viewed it in the same light. My reason for this belief has been personal visions and experiences. (Flux Europa)

Some people might consider this attitude to reinforce the objectification of the female as a tool for the progress of the male’s creative work, and in this way Taylor might not (again) fit into the mold of political correctness. On the other hand, Taylor’s words might describe a timeless honor of the female, which transcends the political and social issues of his lifetime.

The final theme, which we will discuss in relation to Taylor’s work is that of a sort of nihilism. Often the 1960s are remembered as a time of change and of hope, of progress. Yet not all modern people agree with the dominant definition of progress as being interlinked with technological development. As Taylor says: “Another recurring theme in our songs is the rapid decline and quality of life in this civilization,” (Flux Europa) and these ideas are especially apparent in Taylor’s desire to both confront the public through his artwork and then attempt to heal it. Further, Taylor, as a folk artist, positions himself so as to be able to interact with the public on a personal level unfettered by notions of grandeur.

Taylor seems to embrace both the Romantic and the disappointment, which often accompanies idealism. When asked about the “symbiosis of tradition and futurism,” (Flux Europa) he summarizes his ideas best:

I very much share this parallel interest, belief, and goal. I perceive that we as a culture, and as individuals, exist within a continuum. Life moves ever on…Quaint anachronisms only serve as a diversion or avoidance of our responsibility to the present reality. But, nevertheless, archaic ethics, instincts and folkways are the necessary factors that will keep us from falling victims to a soulless technology. Perennial wisdom provides us with the necessary guidelines and wisdom, which have proven efficacious to our survival as a genotype. They are the most valuable baggage we can carry with us as human beings. Disregard, ignore or be ignorant of who we are, what we are, and why we are, and our destination will soon be the dustbin of history…Those who forget the past forfeit the future. They become isolated atoms careening in a void of uncertainty; the perfect denizen of the New World Order. A convenient, compliant and interchangeable work unit. (Flux Europa)

He then tries to resolve the issue, referencing the eternality of existence, which coexists with the very real existence of temporal reality:

Conversely, time moves forward and we as a people must keep pace with its demands. Each age and era has its own priorities, problems and aspirations. Perennial wisdom must be employed and applied so that we have a firm foundation for the future. Once we have achieved that, we can then do as Pound so succinctly wrote: “Make It New”. (Flux Europa)

Robert Taylor has taken it upon himself to voice the message of the eternal through his visual artwork. His influences reflect the multiculturalism of 20th century America as well as his desire to connect with, honor, and carry the torch of his own European heritage. He has used the postmodern tool of appropriation, yet remained true to his identity as a folk artist who seeks not to capitalize upon the work of others, but to translate his spiritual views to the outside world. While many artists may prefer to avoid the infamy some of his work has caused, one cannot deny that Taylor’s representations of his inner exploration caused lasting repercussions on the material world. It is this transformative effect, which, arguably, all artists strive for, but which is undoubtedly fundamental to any political, social or spiritual revolution.

[1] The Process, or, The Process Church of the Final Judgment, is a doomsday offshoot of Scientology, which, arguably, subverted common Christian figures for new archetypal purposes. (Mamatas) At its height in popularity in the 1960s and 70s, the Church ran many coffee shops, one of which hosted Taylor’s musical group Changes in his native Chicago. (“Where It All Began”)

How can the “redefinition of boundaries” in the visual arts, as Lisa Phillips puts it (177), without tearing them down completely, be considered revolutionary? Unless you idealize opportunism and artificiality, the implication that the repackaging of a supposed counter-culture and marketing it to the masses is little more than a path to self-aggrandizement is almost as offensive as John Carlin’s use of the Beatles to illustrate counter-culture music or his statement that Bob Dylan was inspired by his “roots” (179)—if this was the case, Robert Zimmerman would have popularized Klezmer music! While these two might serve well as examples of postmodern appropriation, their era-specific façades and commercial success fail to indicate any deeper exploration of identity within the newly expanded boundaries available to them.

If the 1960s are to possess any true value as a radical period in the history of the visual arts in America, one must turn her or his attention away from the purveyors of vacuous, anonymous art and focus on artists who had the courage to express themselves according to the identity which simply existed within their beings—no matter how unfashionable—through a process, not of redefinition, but of self-discovery.

Robert N. Taylor is one such artist, a folk artist who consciously rejected the path of a conventional, American, white, male yet found little solace in the trends which informed a typical “hippie,” at last finding his own identity upon which he built his unique body of pen and ink drawings. In his own words:

We felt constricted under the thumb of a debased age in which advertised slogans supplanted poetry, contractual agreements replaced love, and televangelism masqueraded as spirituality. Unlike that alien and decadent garb of the Guru cults from the East, the Process[1] had a distinctly Western, Neo-Gothic exterior: Neatly trimmed shoulder length hair and equally neat beards, all set-off by tailored magician’s capes with matching black uniforms. (“Where It All Began”)

Taylor’s father, who, according to Taylor, was “very much a heathen and very anti-Christian,” (Flux Europa) initially fostered this interest in the West and this influence inspires and colors all of Taylor’s creative work.

Originally working as a copywriter and art director for a major advertising firm, and then aligning himself with the artist group The San Francisco Visionaries, (Flux Europa) Taylor developed a personal visual language with which to voice his spiritual views. He filtered ancient European symbols through his graphic arts training and the psychedelic sensibility of the time in order to create pieces, which are both timeless and contemporary. The later work Celtique Egg #3 (see figure 1) will serve as our example and help us follow the streams of influence which comprise Taylor’s work and which eventually lead to the heart of his identity as an artist.

At initial viewing, one is overwhelmed by a seemingly incomprehensible tangle of colors and shapes, which, over time, begin to order themselves according to patterns of colors and symbols. This need for a meditative approach by the viewer is intentional and reflects the creator’s own psychological process, which we will explore later. The use of flat colors against a black backdrop reflects the “poster style” popular in the 1960s psychedelic art and which Taylor employed in his professional life. This image could very well be reproduced in large numbers by silk screen as if Taylor and his peers were making a grassroots effort to promote a new age to the public at large.

The colors themselves, however, while bright and vibrating off the page, do not confront the viewer like those of a propaganda poster do. The array of primary, fluorescent, and pastel colors, in fact, prevents the viewer from forming any sort of conclusive bias based on traditional psychological or emotional associations with color and instead draws the viewer into a new kind of world which holds endless possibilities. The use of black as the interior of this “egg” does seem to employ the familiar symbolism of the eternal, though, and as such, echoes the aforementioned sentiment. The colorful lines enclose the eternal egg like a protective layer while providing pathways by which the viewer can explore it.

But is it that eternity appears in the shape of an egg, or do the pathways delineate the eternal through a shape, which is conceivable by man? Is it possible that the paths themselves are eternal? The egg shape of the image suggests a unity of the notions of the eternal and of creation and that by traversing the pathways of creation, man circumnavigates and parallaxes the eternal.

The symbols which create the “paths” on the surface of the black eternal indicate that these paths parallel the destination of eternality itself as well as lead to it: the paths and the destination are nearly synonymous. This is most clearly demonstrated in the frequent references to the Celtic knot and the arrows. Celtic knots are designs which are constructed in a way so that each line element connects back with itself, and are thus unending, a reference to the eternal. Taylor takes this idea further by arranging them side by side in order to create representations of the mathematical infinity sign, ∞. Carrying this concept out on several pattern layers recalls the infinite character of a fractal, the artistic representation of which is also popular in psychedelic art.

Regarding the arrows, they jut out from crosses and point, like road signs, to tiny, black dots, which seem to be doorways into the eternal. In the context of creation, the arrows’ rounded, uneven heads could be interpreted as phallic symbols. Interestingly, the arrows are ringed by the abovementioned infinity signs, essentially creating circles with dots—an ancient sun symbol. The variation of the swastika symbol, which comprises the Celtic knots, reiterates the sun motif and finds its way into many of Taylor’s drawings. Without going into the myriad symbolic associations cultures have and have had with the sun, it is sufficient to consider its cyclic nature.

In fact, Taylor has such a fascination with the spinning cross, he outlined its extensive history over ten pages in George Petros’ Exit Collection (see figure 2), in which one notes the swastika’s “cosmic origins” and its meaning as a, “Four Directional Unfolding of Space and Time;” yet such content caused the book to be banned in Germany. So while Taylor was, “…simply showing the longevity of this symbol, and that it got frozen in a fourteen-year time slot…” (Art That Kills, 173) he is aware of the ramifications of his actions. In an interview with Petros he explains, “If I’ve left a path of destruction behind me, it wasn’t intentional per se, but I do like to tweak people…I have the ability to manipulate reality around you.” (Art That Kills, 173) Thus, by reclaiming this appropriated and then stigmatized symbol, Taylor conveys the never-ending turning of time in a way which provokes people, even to the point of gaining attention from a governmental body.

Taylor carries his meditation on eternality through to his pictorial history of another, better accepted symbol: pi. He summarizes, “…the history of Pi is also the story of man’s eternal fascination with the circle, and like the circle, this fascination has no beginning and no end.” (Exit, 195) That the survey of pi lies within a few pages of that of the swastika, it almost seems ludicrous that a couple of lines arranged in a particular order could raise so many concerns, while lines arranged differently, with a nearly comparable impetus behind them, hardly cause notice. Taylor’s interest in diagrams and, in a way, diagramming the universe, seems to be a way for him to carry on the tradition of diagrammatic art made by alchemists, whom he cites as a direct influence. (Flux Europa)

But the use of symbolism in Taylor’s work goes even further: “Symbols can be modified in their meaning, but you can’t suppress them—because they come from within.” (Art That Kills, 173) He further explains in an interview with Flux Europa how the writings of Ezra Pound on Chinese and Japanese characters may have subconsciously influenced his work: Ezra Pound and the Imagist poets sought to refine or distill the meanings of words as precisely as possible, and it is possible to say that a symbol is this concept taken to the extreme.

Similarly, in a personal conversation with the author in 2008, Taylor noted enjoying the challenge of shaping his poems in order to further convey the meaning of his words. He tells Flux Europa, “The first pattern poems I encountered were being done by a very fine poet, Robert Dougherty, who created poems that took the shape of the subject they described. This was all done with a typewriter. Some years later I began doing similar typographical experiments with hand calligraphy and stipple pen technique.” These examples show the interplay between language, character, symbol, and visual representation, and how Taylor, who works predominantly as a poet, bridges his writing and visual work.

Another visual model Taylor uses in his work is the mandala. As geometric diagrams of the universe, mandalas are meditation tools for both those who create them and those who view them. Taylor references Jung and explains, “The making of mandalic art is an attempt to find one's way back to the centre of things; it is a yearning for totality and completeness.” (Flux Europa) So, again, what might first appear to be an incoherent web in the work Celtique Egg #3, is actually the result of a meditative process performed by Taylor, in which he has drawn upon various traditions, incorporated symbols which hold personal meaning, and created a work which can then be experienced by others who may also gain some understanding of the nature of existence according to Taylor.

The egg shape present in the egg series demonstrates a deep respect for the female, which comprises an equal half of the creative process. The role of the female in Taylor’s work is an eternal one, which could, arguably, reflect the progress made during the 1960s in the area of women’s rights yet which is tempered by a more traditional, romanticized, male view of the female. Regarding the inspiration for his writing, which seems to apply to his drawings, he states:

The primary source is the Muse. I do not mean 'The Muse' in a metaphorical sense to describe inspiration in a poetic manner, but in a literal sense - a spiritual guide whose touch bestows the gift of inspiration, a Goddess concerned with poetry and muse-ic. My views are similar to the views of the poet Robert Graves, who believed in a Muse and felt that she was the source of all poetry and poetic inspiration. All traditional, archaic cultures seem to have viewed it in the same light. My reason for this belief has been personal visions and experiences. (Flux Europa)

Some people might consider this attitude to reinforce the objectification of the female as a tool for the progress of the male’s creative work, and in this way Taylor might not (again) fit into the mold of political correctness. On the other hand, Taylor’s words might describe a timeless honor of the female, which transcends the political and social issues of his lifetime.

The final theme, which we will discuss in relation to Taylor’s work is that of a sort of nihilism. Often the 1960s are remembered as a time of change and of hope, of progress. Yet not all modern people agree with the dominant definition of progress as being interlinked with technological development. As Taylor says: “Another recurring theme in our songs is the rapid decline and quality of life in this civilization,” (Flux Europa) and these ideas are especially apparent in Taylor’s desire to both confront the public through his artwork and then attempt to heal it. Further, Taylor, as a folk artist, positions himself so as to be able to interact with the public on a personal level unfettered by notions of grandeur.

Taylor seems to embrace both the Romantic and the disappointment, which often accompanies idealism. When asked about the “symbiosis of tradition and futurism,” (Flux Europa) he summarizes his ideas best:

I very much share this parallel interest, belief, and goal. I perceive that we as a culture, and as individuals, exist within a continuum. Life moves ever on…Quaint anachronisms only serve as a diversion or avoidance of our responsibility to the present reality. But, nevertheless, archaic ethics, instincts and folkways are the necessary factors that will keep us from falling victims to a soulless technology. Perennial wisdom provides us with the necessary guidelines and wisdom, which have proven efficacious to our survival as a genotype. They are the most valuable baggage we can carry with us as human beings. Disregard, ignore or be ignorant of who we are, what we are, and why we are, and our destination will soon be the dustbin of history…Those who forget the past forfeit the future. They become isolated atoms careening in a void of uncertainty; the perfect denizen of the New World Order. A convenient, compliant and interchangeable work unit. (Flux Europa)

He then tries to resolve the issue, referencing the eternality of existence, which coexists with the very real existence of temporal reality:

Conversely, time moves forward and we as a people must keep pace with its demands. Each age and era has its own priorities, problems and aspirations. Perennial wisdom must be employed and applied so that we have a firm foundation for the future. Once we have achieved that, we can then do as Pound so succinctly wrote: “Make It New”. (Flux Europa)

Robert Taylor has taken it upon himself to voice the message of the eternal through his visual artwork. His influences reflect the multiculturalism of 20th century America as well as his desire to connect with, honor, and carry the torch of his own European heritage. He has used the postmodern tool of appropriation, yet remained true to his identity as a folk artist who seeks not to capitalize upon the work of others, but to translate his spiritual views to the outside world. While many artists may prefer to avoid the infamy some of his work has caused, one cannot deny that Taylor’s representations of his inner exploration caused lasting repercussions on the material world. It is this transformative effect, which, arguably, all artists strive for, but which is undoubtedly fundamental to any political, social or spiritual revolution.

[1] The Process, or, The Process Church of the Final Judgment, is a doomsday offshoot of Scientology, which, arguably, subverted common Christian figures for new archetypal purposes. (Mamatas) At its height in popularity in the 1960s and 70s, the Church ran many coffee shops, one of which hosted Taylor’s musical group Changes in his native Chicago. (“Where It All Began”)

Works Cited

Mamatas, Nick. “The Process Church of the Final Judgment.” 28 July 2002. Disinformation. <http://old.disinfo.com/archive/pages/dossier/id275/pg1/ index.html>. Web. November 2009.

Petros, George. Art That Kills: A Panoramic Portrait of Aesthetic Terrorism 1984-2001. Creation Books, 2008. Print.

Petros, George, ed. The Exit Collection. New York: Tacit, 1998. Print.

Phillips, Lisa. The American Century, Art & Culture 1950-2000. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1999. Print.

Taylor, Robert N. “Where It All Began.” History Page on the Official Changes Website. 30 July 2009. The Official Changes Website. <http://www.nmia.com/~thermite/ history/olderbio.html>. Web. November 2009.

Taylor, Robert N. Interview by e-mail. Flux Europa Magazine. February-April 1997. Web. November 2009.

Mamatas, Nick. “The Process Church of the Final Judgment.” 28 July 2002. Disinformation. <http://old.disinfo.com/archive/pages/dossier/id275/pg1/ index.html>. Web. November 2009.

Petros, George. Art That Kills: A Panoramic Portrait of Aesthetic Terrorism 1984-2001. Creation Books, 2008. Print.

Petros, George, ed. The Exit Collection. New York: Tacit, 1998. Print.

Phillips, Lisa. The American Century, Art & Culture 1950-2000. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1999. Print.

Taylor, Robert N. “Where It All Began.” History Page on the Official Changes Website. 30 July 2009. The Official Changes Website. <http://www.nmia.com/~thermite/ history/olderbio.html>. Web. November 2009.

Taylor, Robert N. Interview by e-mail. Flux Europa Magazine. February-April 1997. Web. November 2009.